The State of the Wye

We are at a “crucial moment in the life or death of the Wye”

The Wye is being killed by the high levels of phosphates that pollute the river causing algal blooms that then starve the fish, plants & invertebrates of oxygen. This leads to a collapse of the whole ‘web of life’ in the river. These algal blooms are growing larger and becoming more frequent. In 2020, a thick algal bloom extended for over 140 miles of the river.

If this goes on, we will lose everything that we treasure about the Wye. It will turn a horrible, ugly green every time it gets sunny. The fish will go, and they will be followed by our kingfishers, our dippers and our herons. It is very, very worrying.

Simon Evans (Wye and Usk Foundation)

There are multiple sources of P (phosphate) pollution but source apportionment modelling suggests that 60-70% of the total phosphate load now comes from agriculture. Phosphate contains valuable nutrients (phosphorous) essential for plant growth and development and is a key ingredient in all fertilisers. When too much nutrient enters the river it causes eutrophication leading to excessive growth of algae and plants which adversely affects the quality of the water as well as damaging the local ecology.

Wye soils are also more P-leaky than many other soils because of their poor ability to hold onto applied P in fertilisers and manures, and pose a high risk of P loss to draining streams.

The Scale of the Problem

“Phosphate limits are already being exceeded at 31 points in the river catchment, with further failures likely in the future.” (River Wye Nutrient Management Plan – Phosphate Action Plan, 2021)

Data, collected by the Friends of the Upper Wye Citizen Science project, with guidance from Cardiff University water quality scientists, found that 46 per cent of 1,993 samples collected from 73 sites along the Upper Wye throughout 2022 contained “high” levels of phosphorus, with 15 per cent “very high”.

In Wales NRW have been able to undertake more sampling and have found that of the 42 sections of the Wye tested 28 had failed their WFD (Water Framework Directive) limits.

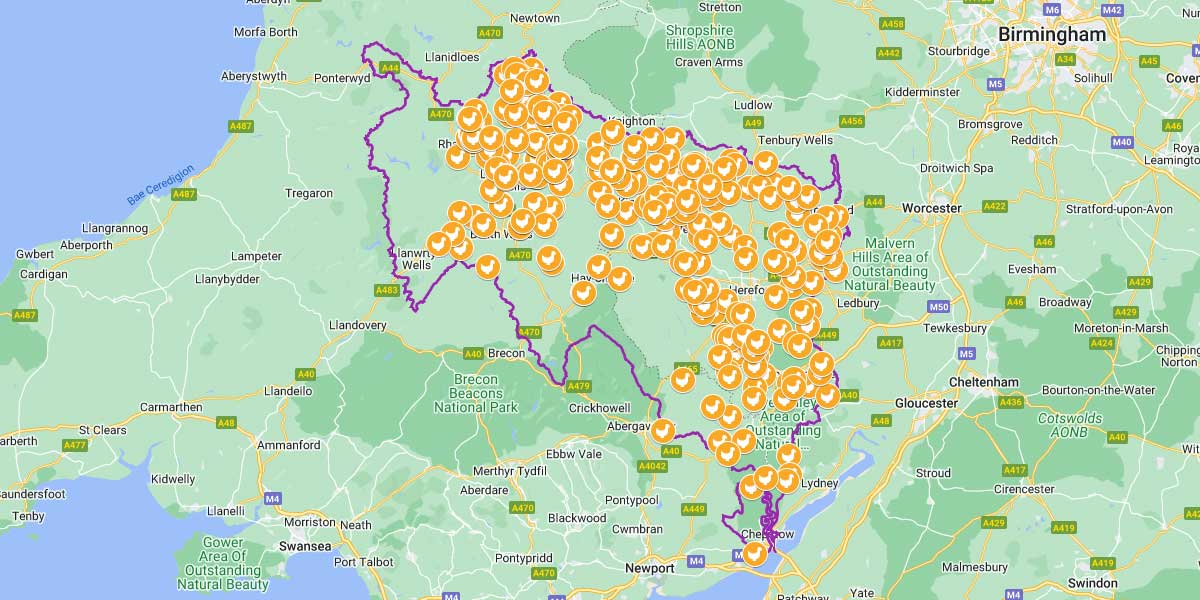

The Link to Intensive Poultry Production

Powys, Shropshire and Herefordshire have become known as “the poultry capital of the UK” because of the scale of poultry production in the area. Cargill subsidiary Avara is Herefordshire’s largest industrial poultry processer. With the expansion of the Avara site in Hereford between 2010 and 2017 came a huge increase in the number of industrial poultry units along the Wye. There is now an estimated 20 million chickens in the Wye catchment at any point in time (4 million in Powys and more than 16 million in Herefordshire).

Of the 6,500 tonnes of phosphate brought into the catchment every year, around 4,000 tonnes arrives as chicken feed. Most of this is excreted. Chicken excrement is rich in phosphates and other chemicals and is spread on the land as fertiliser to help crop growth. This then leaches off into the river, turning it into “pea soup”.

Whether farmers follow the rules or not, eventually the phosphate, nitrate and other pollutants the chicken manure contains end up in the water.

The map below, created by Brecon and Radnor CPRW, shows the locations of Poultry Units in the Wye Management Catchment Area. “The density of these developments has reached a level unmatched in Europe”.

Avara Foods & Cargill Inc.

What do Avara – Cargill say?

In 2013, Cargill won a deal to supply chicken to Tesco, the UK’s biggest supermarket. Joining forces with Faccenda to create Avara Foods, this led to a huge expansion of their operations.

Avara is now the third-largest poultry processor in the UK, two million chickens are processed at its factory in Hereford every week. As a result 160,000 tonnes of manure is produced annually by Avara’s 120 supply farms.

John Reed, Agricultural Director for Avara Foods Ltd, estimated that the company is responsible for approximately 16 million chickens in the catchment, “we recognise that the use of our chicken litter on land in the Wye catchment does have an impact.”

This year Avara published it’s Sustainable Poultry Road Map which promises that “By 2025, our supply chain will not contribute to excess phosphate in the River Wye”.

There are concerns that Avara will be dependent on large scale, ‘novel’, but untested, Anaerobic Digesters (AD) to achieve this (see below ‘The Problem with ADs’).

The Oklahoma Case

In a long-running case in Oklahoma Avara’s parent company Cargill have recently been found guilty of knowingly polluting the river Illinois. The judgement made clear that in the 1980s Cargill knew full well that spreading chicken litter in the catchment would destroy the river. So it is clear that Cargill have known for many years what the impact of their chicken business would be on the Wye.

Owned by a family of 14 billionaires Cargill’s turnover was $165 billion in 2022. Cargill are widely known as ‘The worst company in the world’ due to their track record of environmental destruction across the globe.

To see history repeating like this is heartbreaking. Where’s the corporate responsibility? They had the knowledge but didn’t clean up their act.

Tom Tibbits, Chair of Friends of the Upper Wye

No More Industrial Poultry Units (IPUs)?

To deal with the mountain of manure that the chickens produce first we have to stop adding more and more each year. So there should be a complete halt to any further increase in the number of industrial poultry units.

The Environmental Audit Committee (EAC) recommends that “new poultry farms should not be granted planning permission in catchments exceeding their nutrient budgets”

In 2022, Natural Resources Wales (NRW) admitted for the first time that manure is causing harm to waterways and states that the “spreading of manure from intensive poultry units” is causing pollution, and that these operations are largely “outside of regulatory control”

The definitive Lancaster University led RePHOKUs study recommends:

- A reduction in the overall number of birds

- The exporting of manure out of the area

- An 80% reduction in poultry manure in the Wye

We also have to deal with what is known as ‘legacy phosphate’ that has accumulated in our soil. In parts of Herefordshire there is such an overload of phosphate in the soil that no more needs to be added as fertiliser to the soil for at least twelve years.

This means we need to stop spreading manure on the land immediately. All manure (from all animals) needs to be shipped out of the county to those parts of the UK that do need it.

The Regulators aren’t regulating

Who are they?

Natural England (NE) and Natural Resources Wales (NRW) ensures the ecology of watercourses remains in good health and sets limits for the level of nutrients.

The Environment Agency (EA) is responsible for enforcing laws that protect the environment. It is a non-departmental public body sponsored by the UK government’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA).

There are rules that apply to fertiliser spreading, particularly for chicken manure and it falls to the EA and NRW to enforce those rules. In England these are ‘Farming Rules for Water’ and in Wales, the ‘Water Resources Regulations’.

What have they been doing?

The simple answer is not a lot. Environment Agency funding has been cut by nearly two thirds since 2010. Between 2013 and 2019 the number of water quality samples taken by the EA fell by 45%. And, to date, the Environment Agency has not prosecuted any farmers or landowners for breaking the rules.

Environment Agency chair Sir James Bevan said the rules were deliberately not enforced for the first couple of years “because the government asked us not to”. He said Defra “asked us to work with farmers through advice and guidance while farmers got used to it”.

Rather worryingly, whistleblower officers at the EA have said funding for pollution investigation and enforcement “has been cut back to such an extent that they cannot do their jobs and the regulator is no longer a deterrent to polluters” and so we have a “regulator that is toothless”.

Defra has said it is planning to reform farm rules towards a more advice-led approach. Bevan’s comments come as data shows Environment Agency testing of English rivers has plummeted to a 10-year low and the failure to sample is the greatest threat to river health.

Across the border Fish Legal challenged Powys County Council for granting planning permissions of two IPUs because the spreading of manure within the Wye catchment was considered ‘not material’. Lord Justice Lewison acknowledged that the council had relied on NRW’s lack of objection but that it was ‘arguably’ an ‘error of law’ that the digestate spreading was not material in this case.

“NRW do not – as far as we are aware – regulate the spreading of digestate – nor is it fully regulated as a permitted activity. So, there are massive regulatory gaps where pollution is likely to occur.”

County Councils, Planning and Policies

In Local Authorities the planning officers and committees make the decision on planning applications. Historically there has been both a policy vacuum and little supplementary guidance in local plans to aid the planners in reaching decisions regarding agriculture and livestock development. IPUs are defined as agriculture, rather than industrial developments and the advice to planners has been to accept an EA permit as proof that there would be no unacceptable pollution. In addition, neither Powys or Herefordshire councils have kept track of the total number of chickens in the area and each application for a new IPU has been taken in isolation with little consideration given to the long term impact of Cargill’s rapid expansion or the cumulative impact of so many birds in the catchment area.

Since 2014, the EA, its partners including Natural England, Natural Resources Wales and local authorities have been working through a Nutrient Management Board (NMB) to find solutions to tackle phosphate levels in the catchment.

We have known about the issues facing the Wye for at least 10 years. Over that period, the agencies have been using light touch regulation, advice and encouragement to try and manage the problem. Yet the rivers are in an even worse state now than before. It is therefore essential that we move onto a new model for managing the river with more powers, stricter regulations and more funding to resolve the issues.

A Water Protection Zone

There is a legal mechanism that achieves this called a ‘Water Protection Zone’. This would lay out a special set of rules for the river together with an enforcement mechanism.

At a Wye Catchment Nutrient Management Board meeting in 2021, partners agreed that this stage had been reached and Herefordshire Council wrote to English Ministers on the Board’s behalf to request the establishment of a WPZ.

The decision was made all the more urgent because of the necessary introduction of a moratorium on housing development. Natural England (NE) advised Herefordshire and Powys Councils that no development should take place in the Lugg catchment that cannot prove beyond reasonable doubt that it will not add more phosphate to the river. Small though it is, housing development inevitably does add phosphate and so development has virtually come to a halt there.

So far the Government has rejected calls for this to be implemented.

Save the Wye continues to campaign for the establishment of a properly resourced, cross border WPZ with full enforcement powers.

The Problem with ADs (Anaerobic Digesters)

It is often the case that planning permission has been given for IPUs that include a waste management plan for the building or export of the manure to an anaerobic digester.

The Need for ADs

Chicken manure is a valuable substance – it can be a source of energy and is very rich in nutrients. However the amount produced in IPUs in the catchment is enormous (160,000T p.a. according to Avara, 330,000T p.a. based on DEFRA figures).

Given that soils in the catchment already contain sufficient nutrients, it is essential that none of this extra nutrient load should go on fields in the catchment. However, there are areas in the East of England where these nutrients can be beneficial. Due to the sheer bulk and weight of the manure, transporting the manure in its raw condition is impractical.

When manure is processed to produce energy, this is classed as ‘green’ and attracts grants in addition to the base value of the energy generated.

Two approaches exist for generating energy from manure: Anaerobic digestion, and Biomass burning, and there are examples of both within the catchment.

Anaerobic Digestion

Anaerobic digestion requires addition of water and often other feedstocks (frequently resulting in crops grown purely to feed an AD, this is usually maize). It takes place at modest temperatures, and generates BioGas which may be used for fuelling transport or to generate electricity. In one case it has been proposed for feeding directly into the mains gas supply, however there are concerns that it may not be pure enough.

The other outputs are ‘digestate’ and wastewater, both of which are high in nutrient content, and being liquid in nature are awkward to handle. Typically they are piped into a trailer then spread on fields, thus achieving nothing in terms of eliminating the nutrient problem and relying on the soil-to-river drainage as a waste disposal system.

Examples in the catchment have shown further problems in regard to hazards and accidents. For e.g. GP Biotec, an anaerobic digester business based on Great Porthamel Farm on the Llynfi. Anaerobic digesters have caused (or been strongly suspected of) Fish kills (e.g. River Mole, Devon, River Teifi, Afon Llynfi, and even the loss of human life (e.g. Avonmouth explosion).

Biomass Pyrolysis

Biomass pyrolysis (Chicken litter burning) requires relatively dry waste, and takes place at high temperatures. The heat produced is typically used to warm a nearby IPU in winter, or for grain drying in the summer.

Ideally a consistent fuel input is used, and the end products are heat, flue gases, and ash. The weight of the ash is approximately 7.5% of the weight of the input, and all the phosphate is concentrated in it, thus making it more practicable for long distance transport.

There are concerns regarding the effects on air quality. Various techniques exist to mitigate this but ‘burning’ is far from simple and difficult to provide assurances of minimal (ideally no) noxious substances in the exhaust. However, control of the combustion process (e.g. dry enough fuel fed in at the right rate) is fundamental and ‘air scrubbers’ may be provided in the exhaust. A modern plant, properly run, can achieve very low emissions containing little beyond water, nitrogen gas and carbon dioxide.

Examples; Whittern Farms operate a biomass boiler system to process the manure from their 500,000 hens

There is concern that instead of helping to reduce the problematic manure mountain, industrial fixes to an industrial problem will be used in planning arguments to try to justify further growth in this industry.

In regard to the manure problem, the planning system is hopelessly contorted, with no single point of responsibility identified for the welfare of the environment, and no allowance within the system for the assessment of cumulative impact.

The draft Minerals and Waste Local Plan states that all new Anaerobic Digestors will be agreed only if fed from their own farm.

Further, the planning system assumes strict adherence to ‘the rules’, which are very rarely enforced and frequently flouted. Thus manure from an IPU or digestate from an AD may readily be provided to an unwitting (or complicit) nearby farmer who will spread it regardless of soil requirements. ‘Rules’ include a specification that soil must be tested for phosphate content at intervals and further phosphate should only be spread where needed. However FRfW (Farming Rules for Water) allow further phosphate-rich spreading if the farmer can claim that the nitrate in the substance was needed.